Scott Hahn is a convert and an apologist well-known in the United States and – due to numerous translations of his books – also in other countries. He abandoned Presbyterianism when, through the study of the Bible and the writings of the Church Fathers, he arrived at the conclusion that the Church established by Jesus Christ is continued in the Catholic Church. The discovery of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist played an important role in the process. After some time also his wife, Kimberley, converted to Catholicism.[1]

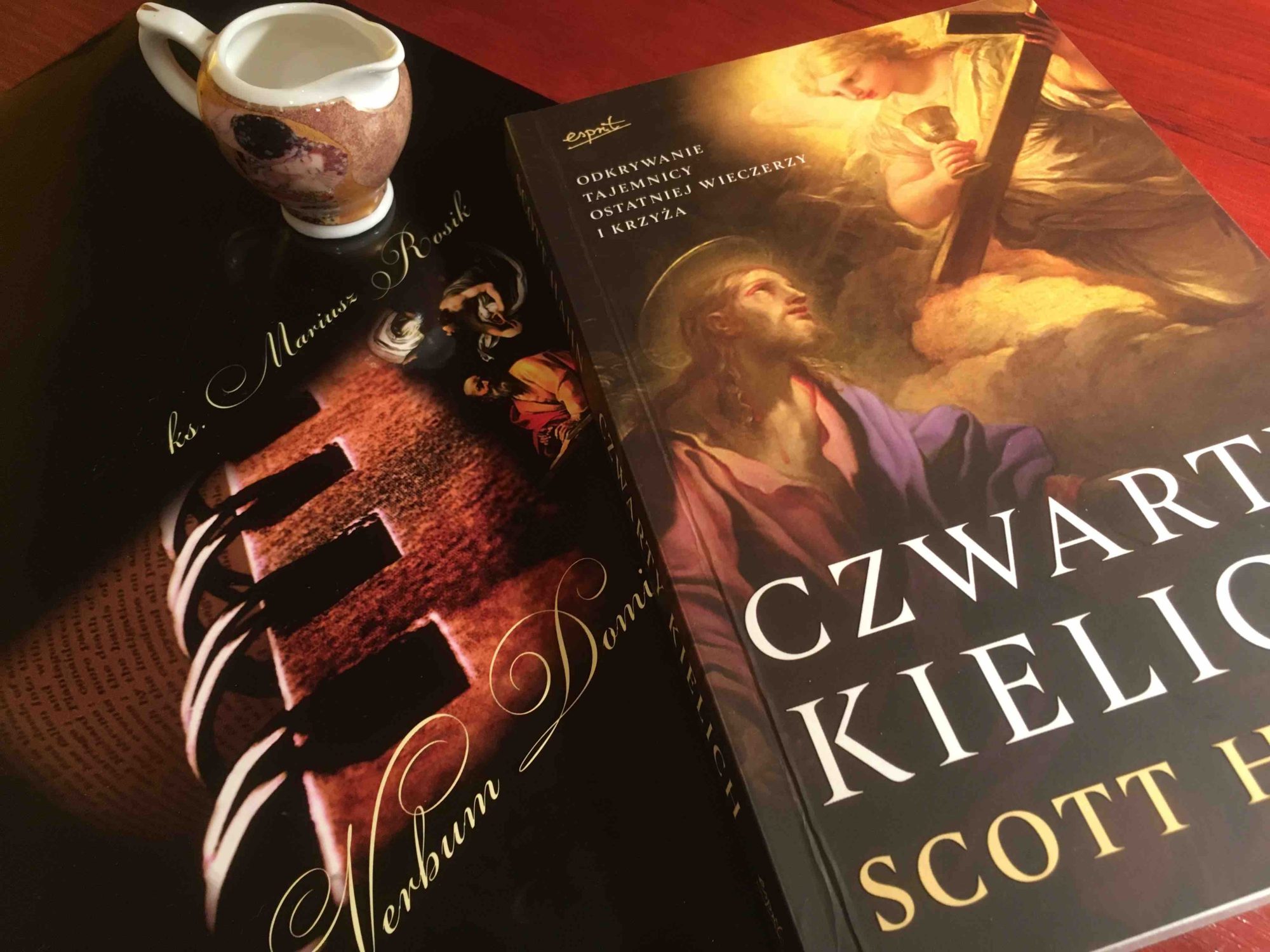

The book by Scott Hahn, which has recently appeared on the Polish publishing market, is entitled The Fourth Cup. Unveiling the Mystery of the Last Supper and the Cross.[2] It is an attempt to answer the question why, during the Last Supper, Jesus violated the ritual and did not offer the last, fourth cup to his disciples. What are we to make of Jesus’ vow: ‘Truly, I say to you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God’ (Mk 14:25)?I was asked by the publishers of the Polish edition of Scott Hahn’s book to write the blurb– a short text to be printed on the back cover. Already at the first reading of The Fourth Cup I realised that I cannot fully agree with the author’s main thesis (the identification of the fourth cup), but the book is filled with so much information, so many valuable observations and relevant exegetic insights that I immediately chose to recommend it to Polish readers.

In the following review article I intend to refer polemically to the theory presented by Scott Hahn, namely, that tasting by Jesus ‘sour wine’ or ‘vinegar’ at the moment of his death on the cross was the fourth cup of the Last Supper (Jn 19:30). Before the presentation of this theory, however, in the first part of the article, the content of the reviewed publication will be critically analyzed (1). Then, in the second part, the shape of the ritual Passover meal will be outlined – naturally only very briefly and in general terms – since it is exactly one of its elements which is the crux of the controversy with Scott Hahn (2). In the third part, Hahn’s arguments for the thesis that Jesus drank the fourth cup right before his death will be enumerated (3). In the fourth part, I will discuss the reservations which the author’s thesis might generate (4). The fifth part will be an attempt at pointing out a different moment when the fourth cup of the Passover meal could be drunk (5). Finally, a suitable summary of both hypotheses will be made and a final conclusion will be formulated (6).

The content – critical analysis

The Fourth Cup starts with Foreword (pp. 9-12) by Brant Pitre, where he briefly outlines the fundamental question raised by Hahn, calling it a ‘riddle’ (p. 9): why, during the Last Supper, Jesus declared that he would not drink of the fruit of the vine again until the coming of the kingdom of God (Lk 22:18; Mt 26:29; Mk 14:25) but later on – right before his death – he asked for wine to be given to him (Jn 19:28).[3]In the Preface (pp. 13-16) the author tells the story of how the book was written, explaining that he wants ‘to avoid repeating tales already told’ in the books Rome Sweet Home and The Lamb’s Supper.[4]

The first chapter of the book (pp. 17-24) is entitled ‘What Is Finished?’ The author ponders here what Jesus had in mind when he cried out from the cross, ‘It is finished’ (Jn 19:30).[5]What was meant – he thinks – was not our redemption since, according to Saint Paul (Rm 4:25), this was achieved through resurrection and not through the death of Jesus.[6]In the chapter entitled ‘Passover and Covenant’ (pp. 25-37) Hahn explains the meaning of the Hebrew words pesach and b’rith by referring to the historical context of Israel’s religious life. Studying the history of the Chosen People, the author arrives at the conclusion that there was a time when the Israelites forgot the obligation to celebrate Passover every year and it certainly is a valuable observation. They were reminded of it by king Josiah who introduced religious reforms. In the chapter ‘A Typical Sacrifice’ (pp. 38-49) Hahn shows the offerings made on the altars in the Jerusalem Temple as a type and foreshadowing of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. He very accurately emphasizes the fact that the paschal offering was of substitutionary nature:

‘The Passover lamb was clearly a substitutionary sacrifice. God had demanded the lives of every firstborn male in the land of Egypt. The lamb’s blood on the doorpost was a sign that the obligation had been satisfied. But, we should ask, why weren’t the Hebrews simply exempt because of their ethnicity? Indeed they were not exempt. They had fallen under the curse because they had violated the covenant. Their ancestors, the sons of Jacob, had sinned grievously by selling their brother Joseph into slavery. The Hebrews of later generations sinned further, and still more grievously, by worshipping the animal-gods of Egypt (see Exodus 12:12, Joshua 24:14–15, Ezekiel 20:7–8)’ (pp.45-46).

The following chapter is entitled ‘Rite Turns’ (pp. 50-61). Hahn accentuates here those moments of the Last Supper in which Jesus departed from the traditional rite of Passover celebration and introduced new elements to it.[7] In the chapter ‘The Paschal Shape of the Gospels’ (pp. 62-73) the author – defying the theories of B. Bokser – offers arguments in support of the view that the Last Supper was the seder, that is the Passover feast.[8]Sound arguments supporting this view bear no relation to the title of the chapter which refers to the paschal shape of the Gospels. It is difficult to say whether the author had in mind the Gospels as literary works or euaggelion understood as the Good News about our salvation. What is of extreme value in this chapter is the discussion of the dating of the Last Supper, where Hahn cites the fundamental biblical works on the subject.[9]

Scott Hahn’s very accurate observation in the next chapter ‘Behold the Lamb’ (pp.74-84) refers to the motif of the sacrificial lamb. While non-Christian commentators often point out the omission by the Evangelists of any mention of a lamb consumed by Jesus and his apostles, Christian exegetes too frequently ignore this question. The motif of the lamb is continued in the following chapter (‘The Lamb from the Beginning,’ pp. 85-94), where fragments of the Book of Revelation and the Letter to the Hebrews, interpreting the motif of the paschal lamb in the Old Testament, are quoted. The author also mentions other types of the sacrifice of Christ present on the pages of the Hebrew Bible.[10]

Another essential element of the menu of the Passover feast – apart from the lamb – was unleavened bread described in the following chapter (pp. 95-105). In this part of his work, the author devotes some attention to Jesus’ Eucharistic discourse (Jn 6). It is a little bit unfortunate that, doing so, he does not mention the fact that the evangelist, referring to the ‘body,’ uses the term σάρξ (Jn 6:53). The explanation of the meaning of the word would greatly enrich the interpretation of the logia which refer to the necessity of eating Jesus’ ‘body.’

Chapter nine of Hahn’s book is crucial for our deliberations. It is entitled ‘The Cups’ (pp. 106-116) and this is where the fourth cup of the Passover feast is identified by the author with ‘vinegar’ or ‘sour wine’ tasted by Jesus right before his death. The topic will be discussed in more detail in the following part of the article. In the chapter entitled ‘The Hour’ (pp. 117-130) Hahn recalls the motif of Johannine tradition, well-known among exegetes, briefly interpreting texts which discuss the ‘hour’ of Jesus (some fragments are analyzed more extensively, like the wedding feast at Cana in Galilee, the conversation of Jesus with the Samaritan woman, and the arrival of Greeks who wished to meet the Teacher of Nazareth). In the chapter ‘The Chalices and the Church’ (pp. 131-142) the author presents the writings of early Christian writers who interpreted the motif of a chalice. We shall find here references to Tertullian and Saint Ambrose of Milan, Saint Jerome of Stridon and Didache, Saint Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Origen, Hippolytus, Chrysostom, Saint Polycarp of Smyrna and Saint Cyprian of Carthage (in that order). The next chapter is devoted to ‘The Paschal Shape of the Liturgy’ (pp. 143-155). The author describes here those moments of the Eucharist which refer directly to Jewish Passover and also to the Passover of Jesus. He makes numerous references to the Book of Revelation. In Chapter thirteen Hahn speaks of the Eucharist as of ‘The Christian Passover’ (pp. 156-166). His reflection is concluded with a call for our Christian life to acquire a more paschal dimension. The yearning is expressed in the last chapter which ends with the words: ‘Only at death is our Passover complete, when like Jesus we can truly say, “It is finished”’ (p. 182). The book concludes with ‘Works Consulted’ (pp. 189-192), or bibliography.

Hahn’s book can be read with bated breath and the reason is that, apart from strictly academic deliberations, the author’s story has a character of his own personal testimony, thanks to which the reader gets to know his journey of conversion from Presbyterianism to Catholicism. As far asacademic arguments supporting the author’s theses are concerned, it is possible to enumerate many more than the ones cited on the pages of The Fourth Cup. The fact that they are missing can be justified by Scott Hahn’s wish not to repeat the ideas discussed in his other and more extensive works on the Eucharist.

Elements of the Passover feast – the crux of the controversy

The heated debate among theologians on whether the Last Supper was a Passover feast prescribed by the Law or not has not been resolved yet, although the answer to this question is fundamental for the interpretation of the accounts depicting the institution of the Eucharist.[11]According to some, there is no doubt that the Last Supper was a typical Jewish Passover meal.[12]Many others, however, reject such a view.[13] R. Bartnicki in the following way justifies the opinion of some scholars on why the Last Supper was not a typical Jewish Passover feast even though it corresponded to it:

‘Mark informs us (Mk 15:34) that Jesus died at nine o’clock, that is at three in the afternoon according to our way of counting the time. John adds that this was Friday, which means that Jesus’ death coincided with the hour when sacrificial lambs were being slaughtered in the Temple. For this reason, Paul referred to Jesus as to the Paschal Lamb of the New Covenant (1Co 5:7). The early church immediately saw in the death of the lamb whose blood protected Israelites from the angel of death (Ex 12:21-33) the foreshadowing of the death of Jesus, which has delivered us from sin and eternal death. Since the Last Supper was held at a time close to Passover, it was natural to look at it as at the Passover of the New Covenant. This is why already in the synoptic Gospels, in the lines describing the event, it is referred to as a Passover meal, although it would be difficult to describe it as such basing only on the description.’[14]

What is the structure of a typical Passover meal? It starts with a prayer called by the Jews kiddush. It is an introductory prayer before the meal, accompanied by the first cup of wine called the sanctification cup (kiddush). What follows is the so-called paschal Haggadah, the story explaining why this night is so important. One of the youngest participants of the feast asks questions about the meaning of the celebration, and the head of the household tells the story of the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. It is very important that the narrative should have the form of a personal testimony. This means that everyone at the table should feel like the participant of the events which are described.[15]The Haggadah is followed by the second cup of wine, called ‘the cup of proclamation’ (Haggadah) and here begins the meal during which the paschal lamb is served as its main course. Then the third cup, called ‘the cup of redemption’ or ‘the cup of blessing’ (beracha), is drunk. After the third cup there comes the time for the recitation of Hallel psalms. Those are psalms from 113 to 118 (the first two were recited earlier),telling the story of the exodus of Israelites from Egypt. The feast should end with the last, fourth cup of wine, called ‘the cup of praise’ (hallel). This was an integral part of the Passover feast, the sign of its ending. The appropriate Mishnaic tractate says: ‘On the eve of Pesah close to minhah one may not eat until nightfall. Even the poorest person in Israel must not eat [on the night of Pesah] until he reclines. And they should give him not less than four cups [of wine], and even from the charity plate’(Pesachim 10:1). Scott Hahn confirms this structure of the Passover meal in his book:

‘The Passover meal was divided into four parts, or courses, and each was accompanied by a cup of red wine mixed with water. The poorest Jews were guaranteed four cups at the community’s expense, so that their experience of the festival should be complete. The rabbis’ instructions governed even the proportion of wine to water in each cup.

As we’ve seen, the meal’s first course consisted of a special blessing (kiddush) spoken over the first cup of wine, followed by the serving of a dish of herbs.

The second course included a recital of the Passover narrative, the questions and answers, and the “Little Hallel” (Psalm 113), followed by the drinking of the second cup of wine.

The third course was the main meal, consisting of lamb and unleavened bread, after which was drunk the third cup of wine, known as the “cup of blessing.”

The culmination of the seder was the singing of the “Great Hallel” (Psalms 114–118) and the drinking of the fourth cup of wine, often called the “cup of consummation”’ (p. 108).

The exegetes who do not approve of the thesis that the Last Supper was a typical Passover meal nevertheless tend to agree that it included its elements.[16]It was a farewell feast of Jesus and his apostles, which came to be interpreted as a Passover meal.[17]There are several important arguments to support this hypothesis:

(1) lack of any reference to eating lamb in the Gospels (see Mk 14:12-16; Lk 22:7-8);[18]

(2) a reference in the Babylonian Talmud that Jesus was hanged on the eve of Passover (Sanh. 43a);[19]

(3) legal impossibility of performing acts which led to the death of Jesus on festive days (Lv 23:5-7);[20]

(4) the impossibility of issuing verdicts or conducting executions on festive days (The Mishnaic tractate Betzah 5:2; Tosefta, Betzah 4:4; Philo of Alexandria, De migratione 91);[21]

(5) research of contemporary astronomers, according to which in 30 AD and 33 AD (probable dates of Jesus’ death), Friday fell on Nisan 14 (as John claims), and not Nisan 15 (as the synoptic Gospels assert).[22]

The above arguments do not, however, contradict the thesis that the Last Supper included elements of a typical Jewish Passover feast[23]and it could be interpreted as the Passover of Jesus, and not the Passover of all the Jews.[24]

The fourth cup according to Scott Hahn

Scott Hahn rightly notices that at a certain moment of the Last Supper Jesus interrupts the ritual of the Passover feast, ‘leaving the liturgy unfinished’ (p. 106). When he takes in his hands the third cup of wine, he says: ‘Truly, I say to you, I shall not drink again of the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God’ (Mk 14:25).The sudden interruption of the feast poses a serious exegetical problem. It should not have happened. Even the poorest Jews had the four cups of wine guaranteed at the expense of the community[25]to make the experience of the festival complete. When Jesus pronounces the words of consecration over the wine, he does it over the third Passover cup.[26]

Why does Jesus end the feast prematurely? Why does he not drink the fourth cup of wine with his disciples? Does he finally end the meal by drinking the last ritual cup of wine? In Scott Hahn’s opinion – he does. The Passover meal is supposed to come to an end at the moment when Jesus tastes vinegar, offered to him right before his death:

‘Finally, at the very end, Jesus was offered “sour wine” or “vinegar” (John 19:30; Matthew 27:48; Mark 15:36; Luke 23:36). All the Synoptics testify to this. But only John tells us how he responded: “When Jesus had received the sour wine, he said, ‘It is finished’; and he bowed his head and gave up his spirit” (19:30)’ (p. 116).

When he tasted the vinegar, Jesus uttered the words, ‘It’s finished.’ According to the author, this is when the Passover of Jesus came to an end.

‘It is finished! At last I had an answer to the preacher’s question. It was the Passover that was now finished! Nothing, it seems, was missing from his seder. All was consummated, completed, brought to conclusion with the wine the Lord consumed with his final breath’(p. 115).[27]

When Jesus before crucifixion was offered ‘wine mingled with myrrh’(Mk 15:23; cf. Mt 27:33) for the first time, he refused to drink it. In Hahn’s opinion, this was the continuation of the refusal to drink wine declared at the Last Supper (p. 115). But when Jesus was offered sour wine or vinegar for the second time (Mk 15:36; Mt 27:48; Lk 23:36; Jn 19:30) and he tasted it, the ritual of the Last Supper as a Passover feast was fulfilled (p.116).

Reservations raised by Scott Hahn’s hypothesis

Scott Hahn conducted a fascinating research project. Having observed that during the Last Supper Jesus omitted the fourth ritual Passover cup, he posed two questions. The first one was: why did it happen? And the second one: can we point out the moment when Jesus finished his Passover and drank the fourth ritual cup? Such a definition of the research objective is extremely valuable and the quest for the answers leads to many interesting discoveries. Nevertheless, even if a number of relevant insights can be found in Hahn’s investigation, it seems that it is possible to follow a different path, defining a different moment of the completion of the Last Supper than the one suggested by the author of The Fourth Cup. Let us first have a look at several points of Hahn’s hypothesis which can raise doubts or which can be questioned.

(1) Jesus’ death is his Passover

According to Scott Hahn, Jesus’ Passover finished when he tasted vinegar or sour wine (Gr. ὄξος). Right after that, ‘hebowed his head and gave up his spirit’(Jn 19:30). The former Presbyterian pastor explains the meaning of the moment in the following way:

‘“When Jesus had received the vinegar,” John tells us, “he said, ‘It is finished’; and he bowed his head and gave up his spirit” (John 19:30). I cannot help, here, but recall the question: What is finished? The Passover is finished. The Passover has been fulfilled. It began the evening before as the Passover of the Old Covenant, but it now finds fulfillment on the cross on Good Friday—as the Passover of the New Covenant’ (p. 166).

Could the moment of Jesus’ physical death be his Passover? The author claims: ‘The Passover is finished. The Passover has been fulfilled’(p. 166). It is difficult to agree with these statements. From a theological point of view, the Passover does not mean the transition from this life to death but the opposite – it is a transition from death to life. Jesus, dying on the cross, passed from mortal life to death. This is the first stage of his Passover, which will ‘finish’ or will be ‘fulfilled’ (to use Hahn’s words) only when glorified Christ will take his place at the right hand of God.

Hahn stops in the middle of the way. It is like saying that the Passover of Israelites ‘finished’ or was ‘fulfilled’ after the angel of death passed through Egypt or after the passage of the Israelites across the Red Sea. No. The Passover was fully complete after their settlement in the Promised Land. For us, Christians, heaven is the Promised Land. So it was in the case of Jesus. The pastor whose words Scott Hahn quotes at the beginning was closer to truth: ‘He pointed out that, in Romans 4:25, Paul said that Jesus was raised for our justification. Thus, the job was “finished” not on Calvary that Friday but at the garden tomb the following Sunday’(p. 21). He was closer to truth but he did not express it in its entirety. The Passover was not fulfilled at the moment of resurrection. It was fulfilled when Jesus ascended into Heaven.[28]A similar message is contained in the Christological hymns in Phillipians 2:5-11[29]or Ephesians 2:2-23.[30]The Passover of Jesus did not finish when the dying convict tasted vinegar – it finished when he was seated at the right hand of God.

(2) „with you”

Scott Hahn seems to ignore Jesus’ statement that he will have the fourth cup in the company of those he started the Last Supper with: ‘From now on, I tell you, I shall never again drink wine until the day I drink the new wine with you in the kingdom of my Father’ (Mt 26:29). The author of The Fourth Cup does not explain how he understands the words ‘with you.’ When Jesus tasted the vinegar or sour wine, he was alone. His disciples were not there. It was only John – the youngest of the apostles – who remained in front of the cross, but the Gospels never mention the fact of him sharing the drink of vinegar or sour wine with Jesus. It is thus highly questionable if tasting vinegar or sour wine at the time of crucifixion could be Jesus’ fourth cup.

(3) „new”

In two among the three synoptic Gospels, Jesus describes the fourth cup as ‘new’: ‘From now on, I tell you, I shall never again drink wine until the day I drink the new wine with you in the kingdom of my Father’ (Mt 26:29); ‘In truth I tell you, I shall never drink wine any more until the day I drink the new wine in the kingdom of God’ (Mk 14:25). Hahn does not explain at any point of his book the nature of this novelty. In the same way as he makes no attempt to discuss the phrase ‘with you,’ he offers no explanation in what sense the fourth cup could be ‘new’ in relation to the other three. It is a clear weakness of the hypothesis which assumes that tasting vinegar or sour wine by Jesus right before his death could be the fourth cup.

(4) Glory of the kingdom of God

In his book, Scott Hahn refers a number of times to Jesus’ refusal to drink wine at the beginning of his Passion: ‘And they offered him wine mingled with myrrh; but he did not take it’ (Mk 15:23; cf. Mt 27:33).Let us quote just two of the references coming from the part of the book most relevant to our considerations. In the chapter entitled ‘The Cups,’ he writes: ‘The narrative does not explain his refusal, but it probably points back to Jesus’ pledge not to drink until his kingdom is manifested in glory’(p. 115). In another place of the same chapter we can read: ‘Jesus had left unfinished the Passover liturgy when he chose to omit the fourth cup. He had stated his intention not to drink wine again until he came into the glory of his kingdom’ (p. 116).

An observant reader of the Gospel may ask: where is the glory? The one whom some considered to be the Messiah and who called himself the king of the Jews has just lost his life. He suffered the most disgraceful death in antiquity.[31] His almost naked body hung on display as a mark of public shame. His closest disciples dispersed. The crowds, which a few days before had chanted ‘Hosanna!,’ changed their cry into ‘Crucify!’ So what does the author of The Fourth Cup mean when he says that the glory of God’s kingdom ‘came’ or was ‘manifested’? It is not clear.

(5) A cup of wine or a sponge filled with vinegar / sour wine

The ritual of the Passover feast encompassed drinking four cups of ‘wine’ (Gr. οἶνος). None of the four descriptions of the institution of the Eucharist, which can be found on the pages of the New Testament, includes the noun ‘wine.’ Only the cups are mentioned. Scott Hahn himself notes that when ‘wine’ is mentioned at Cana in Galilee, the sign foreshadows the institution of the Eucharist during the Passover meal (pp. 122-124). Thus, it seems logical that when the same John the Evangelist, who had related the events at Cana, sat down to describe the offer of a drink at the moment of Jesus’ crucifixion, he should have used the word ‘wine’ and not ‘vinegar’ or ‘sour wine (Gr. ὄξος).’ His report would then be more consistent in theological terms. But the beloved disciple writes: ‘A jar of sour wine stood there; so, putting a sponge soaked in the wine on a hyssop stick, they held it up to his mouth’ (Jn 19:29). Since John uses the word ὄξος instead of οἶνος, it seems questionable whether he really meant the fourth cup of the Passover meal.

The fourth cup at the heavenly banquet

Keeping in mind all doubts which the otherwise very interesting hypothesis of Scott Hahn may raise, I would like to propose a different theological reading of the moment when Jesus drank his fourth cup of wine and thus completed the ritual of the Passover feast. The first three cups were drunk in the Upper Room: the first one followed the prayer called kidush, the second one followed the paschal Haggadah, and while drinking the third cup, Jesus accomplished what we nowadays call the ‘consecration’ of the wine: he changed the wine into his blood. Immediately after that, he left the Upper Room and went to the Garden of Olives, where he prayed: ‘Father, if you are willing, take this cup away from me. Nevertheless, let your will be done, not mine’ (Lk 22:42).

Speaking about the cup, he meant his death.[32]Since, while pronouncing the words of the institution of the Eucharist and passing the cup to his disciples, he said that this was his blood ‘poured out for you’ (Lk 22:20) and ‘for many’ (Mk 14:24; Mt 26:28), this means that the third cup was identified with his death.[33] Dying on the cross, Jesus poured his blood (‘there came out blood and water’; Jn 19:34) – the same which he had given to his disciples to drink during the Last Supper. This is true that at Gethsemane he prayed, ‘take this cup away from me,’ but he knew that God’s will would be fulfilled so he immediately added ‘let your will be done’ (Lk 22:42). Since he was certain that God’s will would ‘be done’ and the Father would not ‘take this cup away,’ in the Upper Room he had already offered to the apostles his blood to drink, in theological sense anticipating his death.

What happened next? Everything that we rightly call the Passover of Jesus, which means his death, resurrection, ascension into heaven and being seated at the right hand of the Father. This is the real Passover – the transition from death into life. It is not possible to comment at this point on the whole passages of the Book of Revelation, but it is enough to recollect the main ideas of the last book of the New Testament. Jesus as the paschal Lamb is glorified by the redeemed (Rv 5:12-14); there is no temple because he himself is the temple (Rv 21:22); the redeemed have washed their sins in his blood poured on the cross (Rv 7:14); and finally the Lamb himself invites guest to the feast: ‘Blessed are those who are invited to the wedding feast of the Lamb’ (Rv 19:9). And during this meal – the wedding feast of the Lamb – Jesus and all who believe in him drink the fourth cup of the Last Supper – the Passover feast.

The answer to the question of when Jesus drank the fourth cup of the Passover feast offered here seems to dispel the doubts raised by the hypothesis proposed by Scott Hahn.

(1) Passover does not only refer to the death of Jesus

The term pesach originally meant for the Jews first the ‘passing’ of the angel of death who killed all the first-born in Egypt; then it meant ‘the passage’ of Israelites across the Red Sea and the desert to Canaan. In Christianity the term broadens its meaning and points at ‘the passage’ of Christ from death to life, encompassing also his resurrection, ascension into heaven and even the descent of the Holy Spirit.[34]Thus it describes the true Passover of Christ – the passage from this world to the Father, to the eschatological kingdom of God. The Eucharist is not only the re-enactment of Christ’s death, but also of his resurrection and ascension into heaven. Catechism of the Catholic Church asserts: ‘By celebrating the Last Supper with his apostles in the course of the Passover meal, Jesus gave the Jewish Passover its definitive meaning. Jesus’ passing over to his father by his death and Resurrection, the new Passover, is anticipated in the Supper and celebrated in the Eucharist, which fulfils the Jewish Passover and anticipates the final Passover of the Church in the glory of the kingdom’(Catechism of the Catholic Church 1340). Jesus’ Passover means ‘passing over to his father by his death and Resurrection.’[35]

According to Catholic theology, the Eucharist commemorates the Passover of Christ. If we accept the explanation of Scott Hahn, who claims that the Passover was fulfilled at the moment when Christ tasted vinegar, then the literal understanding of the hypothesis does not even encompass the death of the Messiah. Jesus uttered the words ‘It is finished’ when he was still alive so even the Passover understood as his death had not been fulfilled yet. Jesus should have said ‘It is finishing.’ But even if we accept that by saying ‘It is finished’ Jesus meant his death, this would mean that, in Scott Hahn’s opinion, the Eucharist only represents the death of Christ. If we assume that the Eucharist represents the Passover of Christ, and the Passover was finished at the moment of his death, it comprises neither resurrection nor ascension into heaven. But the Passover of Christ was fulfilled through his ascension. What happened on the cross was the ‘fulfillment’ of the earthly mission of historical Jesus.

(2) „with you”

In the words of Jesus himself, he was supposed to drink the last ritual cup with those who constituted the germ of the emerging Church (Mt 26:29). In front of the cross, apart from John the Evangelist, there remained no one from among the disciples who were present in the Upper Room during the Last Supper. Thus the theory that the statement from Mt 26:29 came true when Jesus tasted vinegar or sour wine offered to him in a sponge cannot be supported. It is fulfilled in the eschatological kingdom in heaven at the Messianic banquet prepared for all those redeemed by the blood of the Lamb. This is why the Book of Revelation mentions ‘a huge number’ or ‘crowd’ (Rv 7:9; 19:1.6) of those who ‘are invited to the wedding feast of the Lamb’ (Ap 19:9).[36]

Jesus promised to finish the Last Supper in the company of the apostles. If for him the Last Supper had finished at the moment of tasting vinegar, when did it finish for his disciples? Hahn does not answer this question because it is impossible to point out the end of the feast within the Gospels. It is necessary to refer to the Book of Revelation where the wedding feast of the Lamb is described (Rv 19:1-10).[37]

(3) „new”

Jesus announced that the fourth cup of the Passover would contain ‘the new wine.’ (Mk 14:25; Mt 26:29) But there is nothing new about the vinegar or sour wine offered to him in the sponge. Everything happens in the finite earthly realm. The first three cups were drunk during Jesus’ earthly life and so is the fourth cup. Jesus is still alive, his death has not come yet, so it is not clear what is new in these circumstances. Moreover, the new wine was supposed to be drunk in the kingdom of God (‘the new wine with you in the kingdom of my Father’; Mt 26:29). According to what Jesus taught, the kingdom of God existed already in his lifetime: ‘the kingdom of God is among you’ (Lk 17:21). When Jesus tasted the vinegar, nothing was changed in the kingdom. There was nothing new. In the same way as it had existed ‘among you’ before, so it did when the sponge touched his lips. But everything was radically changed after his resurrection and ascension into heaven. This stage of the kingdom can be described as totally new. This is an eschatological kingdom, eternal, everlasting. Such a kingdom Jesus had in mind when he announced drinking ‘the new wine’ in the kingdom of God.[38]

Jesus mentions ‘the new wine’ in Mark (Mk 14:25) and Matthew (Mt 26:29). His announcement sounds slightly different in Luke: ‘from now on, I tell you, I shall never again drink wine until the kingdom of God comes’ (Lk 22:18). The conclusion which might be drawn from here is that, when Jesus and the apostles celebrated the Last Supper, the kingdom of God had not arrived yet. How should we then understand the earlier utterance in the same Gospel according to Luke: ‘the kingdom of God is among you’ (Lk 17:21)? The only interpretation possible is that after the resurrection of Jesus there comes a totally new stage of the existence of the kingdom of God and that in that new kingdom Jesus and those who believe in him will drink the fourth cup of the Passover feast.

(4) glory

Scott Hahn is right when he says that Jesus will drink the last cup of the Passover meal when the kingdom of God manifests itself in glory. This is the Book of Revelation, with its descriptions of the eschatological kingdom, which resounds with glory. Let us quote only three lines from among many passages: ‘Worthy is the Lamb that was sacrificed to receive power, riches, wisdom, strength, honour, glory and blessing’ (Rv 5:12); ‘To the One seated on the throne and to the Lamb, be all praise, honour, glory and power, for ever and ever’ (Rv 5:13);‘Amen. Praise and glory and wisdom, thanksgiving and honour and power and strength to our God for ever and ever. Amen’ (Rv 7:11).The adoration resounds most strongly at the wedding feast of the Lamb: ‘Let us be glad, joyful and give glory to God, because this is the time for the marriage of the Lamb’ (Rv 19:7). It is not necessary to quote here the whole fragment of Rv 19:1-10 to see that it is suffused with the motif of the glory of God’s kingdom.

What is more, the motif is in perfect harmony with Saint John’s theology of glory. Scott Hahn is right when he writes that the sign at Cana in Galilee was the foreshadowing of the Eucharist. John finishes his account with the words: ‘This was the first of Jesus’ signs: it was at Cana in Galilee. He revealed his glory, and his disciples believed in him’ (Jn 2:11). Many Church Fathers interpreted the event as a symbol of the wedding of Christ with his Church. The feast described in Rv 19:1-10 should be interpreted in the same way. This is the wedding feast of the Lamb – the nuptials of Christ and his Church. If the event at Cana foreshadows the institution of the Eucharist during the Last Supper, then Rv 19:1-10 must refer to the Last Supper, too; all the more that the feast described there constitutes its real ending.

(5) „Take this cup away from me” (Lk 22:42)

We can see certain ambivalence in Jesus’ prayer at Gethsemane. On the one hand he asks the Father to take away the cup of death, and on the other hand he prays to fulfill his Father’s will: ‘Father, if you are willing, take this cup away from me. Nevertheless, let your will be done, not mine’ (Lk 22:42). Jesus was aware of the fact that he would pour his blood and that is why he had offered it to the apostles in the third cup of the Last Supper. Like every human being, he was afraid of death and was asking to be saved. At the same time, he knew death was inevitable if God’s plan of redemption was to be fulfilled.

The ambivalence is reflected in the refusal to drink wine at the beginning of the Passion (‘They offered him wine mixed with myrrh, but he refused it’; Mk 15:23) and the consent to drink it right before dying (‘I am thirsty’; Jn 19:28). The refusal corresponds with the words of the prayer ‘Take this cup away from me’ (Lk 22:42). The cry ‘I am thirsty’ corresponds with the consent to fulfill the will of the Father to the very end. In this way, the content of the prayer in the Garden of Olives correlates with what happened at crucifixion. In the Garden of Olives Jesus prayed for salvation from death but eventually agreed to accept it as the will of his Father. At the time of crucifixion, Jesus initially refused to drink wine but finally tasted it to express his submission to the Father.

Conclusions

Scott Hahn’s book is an attempt to answer the question of when Jesus drank the fourth ritual cup of the meal and thus finished the Last Supper. The author identifies the moment of tasting by crucified Jesus vinegar or sour wine offered to him in the sponge as the true ending of the meal. He supports the theory with many arguments. Most of them can, however, be questioned and a number of counterarguments can be quoted. Careful rereading of the evangelical stories describing the passion and death of Christ and the events following them provide a basis for a different identification of the fourth cup of the Last Supper.

After his resurrection, Jesus ascended into heaven. There he is still drinking the fourth cup of the Last Supper which was a Passover feast. This is where his Passover ends – at his Father’s house. Saint John saw it: ‘Then I saw, in the middle of the throne […] and the circle of the elders, a Lamb standing that seemed to have been sacrificed; it had seven horns, and it had seven eyes, which are the seven Spirits that God has sent out over the whole world’ (Rv 5:6). The word used here to describe the elders is presbyteroi, ‘priests.’ They are celebrating the final moment of Eucharistic liturgy in the presence of ‘a Lamb standing that seemed to have been sacrificed.’ ‘Seemed’ sounds hesitant, because resurrected Jesus lives as the One who has full authority (horns) and full knowledge (eyes), and who along with his Father sends the Holy Spirit to this world in order to help us pass to where he already is.

According to Saint Paul, Christ is our Passover: ‘Our Passover has been sacrificed, that is, Christ’ (1 Co 5:7). Our Passover will be finished when we accept the fourth cup of wine from the hands of the Lord, and then we will stay with him forever (1Th 4:17). The moment is preceded by every Eucharist we participate in. The Last Supper continues. It started in the Upper Room and is still going on, making Jesus’ Passover (his passion, death, resurrection and ascension into heaven) present on the altars of the whole world. And so it will continue until the time of parousia. Then all the redeemed will finish their Passover – the passage from this world to the glory of the eschatological kingdom of God. And there the wedding feast of the Lamb will go on, during which all the redeemed will drink the fourth cup of the Last Supper.

Summary

The article begins with the presentation of the content of the book by Scott Hahn entitledThe Fourth Cup. Unveiling the Mystery of the Last Supper and the Cross. Then the author of the article outlines the shape of the ritual Passover meal, assuming that the sacrament of the Eucharist was instituted by Jesus during a meal similar to a Passover feast. Having delineated the context, he presents Scott Hahn’s hypothesis which identifies the fact of accepting by Jesus the drink of sour wine or vinegar right before his death with drinking the fourth cup of the Passover feast. The hypothesis has been critically analyzed and an alternative hypothesis has been proposed, according to which Jesus drinks the fourth cup of the Last Supper in the eschatological kingdom of God.

Key-words: the Last Supper, the Eucharist, the Passover meal, the fourth cup

Bibliografia

Barrett C.K., „Luke XXII.15: To Eat the Passover”, Journal of Theological Studies 9 (1958) 305-307.

Bartnicki R., „Eucharystia w Bożym planie zbawienia”, Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny 50 (1997) 2-16.

Bartnicki R., „Eucharystia w Nowym Testamencie”, Warszawskie Studia Teologiczne 4 (1991) 14-41.

Bartnicki R., „Ewangeliczne opisy męki w aspekcie literackim, teologicznym i kerygmatycznym”, Studia z biblistyki, III (red. J. Łach) (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo ATK 1983) 103-143.

Bartnicki R., „Ostatnia Wieczerza a męka Jezusa”, Męka Jezusa Chrystusa(red. F. Gryglewicz) (Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 19863) 65-85.

Bartnicki R., „Ostatnia Wieczerza nową Paschą Jezusa”, Warszawskie Studia Teologiczne 33 (2015) 10, 6-43.

Bartnicki R., „Pascha żydowska a chrześcijańska ofiara eucharystyczna. zarys historii obrzędu”, Studia Theologica Varsaviensia 18 (1980) 1, 97-124.

Bartnicki R., To czyńcie na moją pamiątkę. Eucharystia w świetle Biblii(Warszawa: Wydawnictwo ADAM 2010).

Beckwith R.T., „The Date of the Crucifiction: The Misuse of Calendars and Astronomy to Determine the Chronology of the Passion”, Calendar and Chronology, Jewish and Christian: Biblical, Intertestamental, and Patristic Studies(Leiden: Brill 2001).

Bokser B., The Origins of the Seder: The Passover Rite and Early Rabbinic Judaism (Berkeley 1984).

Bonnard P.-É, „Pascha”, Słownik teologii biblijnej(red. X. Léon-Dufour) (Poznań – Warszawa: Pallotinum 1973) 646-651.

Brown R., The Death of the Messiah: From the Gethsemane to the Grave. A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels(Anchor Bible Reference Library, II; New York – London – Toronto – Sydney – Auckland: Doubleday 1994).

Bruce F.F., The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to Ephesians(The New International Commentary on the New Testament) (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 1998).

Bucchan Gray G., Sacrifice in the Old Testament: Its Theory and Practice(New York: Ktav Pub. House 1971).

Dalman L., Jesus – Jeshua: Studies in the Gospels(tłum. P.P. Levertoff) (New York: Literary Licensing 1929.

Danby H., The Mishnah(Oxford: Oxford University Press 1933).

Daube D., The New Testament and Rabbinic Judaism (Peabody: Hendricksons Publishers 1994).

Dunn J.D.G., Jesus Remembered (Christianity in Making, I; Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 2006).

Fredriksen P., Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews(New York: Pan Macmillan 1999).

Gnilka J., Jezus z Nazaretu. Orędzie i dzieje(tłum. J. Kudasiewicz) (Kraków: Znak 1997).

Hahn S., Czwarty kielich. Odkrywanie tajemnicy Ostatniej Wieczerzy i krzyża(tłum. D. Krupińska, przedmowa: B. Pitre) (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Esprit 2018) = The Fourth Cup: Unveling the Mystery of the Last Supper and the Cross(Steubenville: Image 2018).

Hahn S. i K., W domu najlepiej. Nasza droga do Kościoła katolickiego(tłum. M. Majdan) (Warszawa: Promic 20092) = Rome Sweet Home. Our Journey to Catholicism(San Francisco: Ignatius 1993).

Hahn S, Uczta Baranka. Eucharystia – niebo na ziemi (tłum. A. Rasztawicka-Szponar) (Częstochowa: Edycja Świętego Pawła 2013) = The Lamb’s Supper. Eucharist as Heaven on Earth (London: Darton, Longman &Todd Ltd. 1999).

Hamilton V., Handbook on the Pentateuch(Grand Rapids: Baker Academic 2005).

Hengel M., Schwemer A.M., Geschichte des frühen Christentums, I, Jesus und das Judentum(Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2007).

Hola K., „Paschalny charakter Ostatniej Wieczerzy a data śmierci Jezusa”, Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny38 (1985) 41-44.

Humphreys C.J., Waddington W.G., „Astronomy and the Date of Crucifixion”, Chronos, Kairos, Christos: Nativity and Chronological Studies Presented to Jack Finegan(red. J. Vardaman, E. Yamauchi) (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns 1989) 165-181.

Humphreys C.J., Waddington W.G., „Dating the Crucifiction”, Nature 306 (1983) 743-746.

Jankowski A., „Eucharystia jako ‘nasza Pascha’ (1Kor 5,7) w teologii biblijnej Nowego Testamentu”, Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny 28 (1975) 89-100.

Jaubert A., The Date of the Last Supper(Staten Island: Alba House 1965).

Jeremias J., The Eucharistic Words of Jesus(tłum. N. Perrin) (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1977).

Kent H.A., „Philippians”, Expositor’s Bible Commentary with The New International Version of The Holy Bible in Twelve Volumes, XI, (red. F.E. Gaebelein) (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House 1984) 93-160.

Köstenberger A., „Was the Last Supper a Passover Meal?”, The Lord’s Supper: Remembering and Proclaiming Christ until He Comes(red. T.R. Schreiner, M.R. Crawford) (New American Commentary Studies in Bible & Theology; Nashville: B&H Academic 2010) 6-30.

Levine A.-J., The Misunderstood Jew: The Church and the Scandal of the Jewish Jesus(San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco 2006).

Ligier K., „De la Cène du Seigneur à la l’Eucharistie”, Assemblée du Seigneur 1 (1968) 15-29.

Maier J., Jesus von Nazareth in der talmudischen Überlieferung(Erträge der Forschung 82; Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1978).

Marshall I.H., Lord’s Supper and Last Supper(Exeter: Paternoster 1980).

Matson M.A., „The Historical Plausibility of John’s Passion Dating”, John, Jesus, and History, II, Aspects of Historicity in the Fourth Gospel(red. P.N. Anderson, F. Just, T. Thatcher) (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature 2009) 291-312.

McKnight S., Jesus and His Death: Historiography, the Historical Jesus, and Atonement Theory(Waco: Baylor University Press 2005.

Marcus J., „Passover and the Las Supper Revisited”, New Testament Studies 59 (2013) 303-324.

Mędala S., Ewangelia według świętego Jana. Rozdziały 13-21(Nowy Komentarz Biblijny. Nowy Testament IV/2; Częstochowa: Edycja Świętego Pawła 2008).

Morris L., The Gospel according to John. Revised (The New International Commentary on the New Testament; Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 1995).

Mounce R.H., The Book of Revelation. Revised (The New International Commentary on the New Testament; Grand Rapids Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 1997).

Pesch R., „Das Evangelium in Jerusalem: Mk 14, 12-26 als ältestes Überlieferungsgut der Urgemeinde”, Das Evangelium und die Evangelien. Vorträge vom Tübinger Symposium 1982 (red. P. Stuhlmacher)(WUNT 28; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1983) 113-155.

Paciorek A., Ewangelia według świętego Mateusza.Rozdziały 14-28(Nowy Komentarz Biblijny. Nowy Testament I/2; Częstochowa: Edycja Świętego Pawła 2008).

Pesch R., „Geht das Abendmahl auf Jesus zurück?”, RU an Höheren Schulen 19 (1976) 2-9.

Pitre B., Jesus and the Last Supper (Grand Rapids – Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 2015).

Pitre B., Jezus i żydowskie korzenie Eucharystii(tłum. M. Sobolewska) (Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM 2018) = Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper (Steubenville: Image 2011).

Pitre B., Jesus, the Tribulation, and the End of the Exile: Restoration Eschatology and the Origin of the Atonement(Tübingen – Grand Rapids: Baker Academic 2005).

Ratzinger J. – Benedykt VI, Jezus z Nazaretu, II, Od wjazdu do Jerozolimy do Zmartwychwstania(tłum. W. Szymona) (Kielce: Wydawnictwo Jedność 2011).

Rosik M., Arka i gołębica. Nurt charyzmatyczny w Kościele katolickim (Kraków: Wydawnictwo eSPe 2019).

Rosik M., Jezus i Jego misja. W kręgu orędzia Ewangelii synoptycznych(Studia Biblica 5; Kielce: Verbum. Instytut Teologii Biblijnej 2003).

Rosik M., Ku radykalizmowi Ewangelii. Studium nad wspólnymi logiami Jezusa w Ewangeliach według św. Mateusza i św. Marka(Wrocław: Polska Akademia Nauk 2000).

Rosik M., Trzy portrety Jezusa (W kręgu Słowa 1; Tarnów: Biblos 2007).

Rucksthul E., Chronology of the Last Days of Jesus. A Critical Study(tłum. V.J. Drapela) (New York – Tournai – Paris – Rome: Desclee Company, Inc. 1965).

Schröter J., Das Abendmahl: Frühchristliche Deutungen und Impulse für die Gegenwart(Stuttgarter Bibelstudien 210; Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk 2006).

Skevington Wood A., „Ephesians”, Expositor’s Bible Commentary with The New International Version of The Holy Bible in Twelve VolumesXI (red. F.E. Gaebelein) (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House 1984) 1-92.

Szymik S., „Żydowska Pascha – Ostatnia Wieczerza – Eucharystia”, Msza Święta – rozumieć, aby lepiej uczestniczyć. Wykład liturgii Mszy(Poznań: Pallotinum 2013) 14-18.

VanderKam J.C., From Revelation to Canon (Boston: Brill 2000).

Witczyk H., „Pascha”, Encyklopedia katolickaXIV (red. E. Gigilewicz i inn.) (Lublin: Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski 2010) 1407-1410.

Witczyk H., „Pascha”, Nowy słownik teologii biblijnej (red. H. Witczyk) (Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL – Jedność: Lublin – Kielce 2017) 666-671.

Wright N.T.,Jesus and the Victory of God(Minneapolis 1996).

Zeitlin Z., „The Last Supper as an Ordinary Meal in the Fourth Gospel,” Jewish Quarterly Review 42 (1951/52) 251-60.

[1]The story of the conversion is told by Scott and Kimberly Hahn in the book Rome Sweet Home. Our Journey to Catholicism(San Francisco: Ignatius 1993).

[2]S. Hahn, The Fourth Cup: Unveling the Mystery of the Last Supper and the Cross(New York: Image 2018).

[3]Brant Pitre described the problem discussed by Hahn in his book Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper(New York: Image 2011), where the Preface had been written by Scott Hahn. Pitre’s more extensive work on the Last Supper is Jesus and the Last Supper (William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company: Grand Rapids – Cambridge 2015).

[4]S. Hahn, The Lamb’s Supper. Eucharist as Heaven on Earth (London: Darton, Longman &Todd Ltd. 1999).

[5]S. Mędala pays no attention to Jesus’ cry in his commentary, focusing only on the gift of the Holy Spirit to the emerging Church; S. Mędala, Ewangelia według świętego Jana. Rozdziały 13-21(Nowy Komentarz Biblijny. Nowy Testament IV/2; Częstochowa: Edycja Świętego Pawła 2008) 248.

[6]See: D. Moo, The Epistle to the Romans (The New International Commentary on the New Testament; Grand Rapids – Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 1996) 288-290.

[7]A more detailed presentation of the changes introduced by Jesus into the sederrite can be found in: M. Rosik, Arka i gołębica. Nurt charyzmatyczny w Kościele katolickim (Kraków: Wydawnictwo eSPe 2019) 351-361.

[8]B. Bokser, The Origins of the Seder: The Passover Rite and Early Rabbinic Judaism(Berkeley 1984) 25-26.

[9]A. Jaubert, The Date of the Last Supper(Staten Island: Alba House 1965); E. Rucksthul, Chronology of the Last Days of Jesus. A Critical Study(New York – Tournai – Paris – Rome: Desclee Company, Inc. 1965); J.C. VanderKam, From Revelation to Canon (Boston: Brill 2000) 81-127.

[10]They are based on Peri Pascha by Melito of Sardis: ‘This is the one who was murdered in Abel, and bound as a sacrifice in Isaac, and exiled in Jacob, and sold in Joseph, and exposed in Moses, and sacrificed in the lamb, and hunted down in David, and dishonored in the prophets […], who was hanged on the tree, who was buried in the earth, who was resurrected from among the dead, and who raised mankind up out of the grave below to the heights of heaven.’

[11]‘If Jesus celebrated his final meal the evening after the Passover lambs were sacrificed in the Temple, then the Last Supper was clearly a Jewish Passover meal, and everything Jesus did and said at that meal needs to be interpreted in that context. However, if Jesus celebrated his final meal the evening before the Passover lambs were sacrificed in the Temple, then the Last Supper was not a Passover banquet, but some other kind of meal’; B. Pitre, Jesus and the Last Supper, 254; I.H. Marshall, Lord’s Supper and Last Supper(Exeter: Paternoster 1980) 57-60.

[12]A. Köstenberger, „Was the Last Supper a Passover Meal?”, The Lord’s Supper: Remembering and Proclaiming Christ until He Comes, (ed. T.R. Schreiner, M.R. Crawford) (New American Commentary Studies in Bible & Theology, Nashville: B&H Academic 2010) 24-25; S. McKnight, Jesus and His Death: Historiography, the Historical Jesus, and Atonement Theory(Waco: Baylor University Press 2005) 259; R. Bartnicki, „Ostatnia Wieczerza nową Paschą Jezusa”, Warszawskie Studia Teologiczne 33 (2015) 10, 16-17; A. Jankowski, „Eucharystia jako ‘nasza Pascha’ (1Kor 5,7) w teologii biblijnej Nowego Testamentu”, Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny 28 (1975) 89-91; K. Hola, „Paschalny charakter Ostatniej Wieczerzy a data śmierci Jezusa”, Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny38 (1985) 41-44; R. Pesch, „Geht das Abendmahl auf Jesus zurück?”, RU an Höheren Schulen 19 (1976) 2-9; L. Ligier, „De la Cène du Seigneur à la l’Eucharistie”, Assemblée du Seigneur 1 (1968) 29; J. Gnilka, Jezus z Nazaretu. Orędzie i dzieje(trans. J. Kudasiewicz) (Kraków: Znak 1997) 372; M. Hengel, A.M. Schwemer, Geschichte des frühen Christentums, I, Jesus und das Judentum(Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2007) 582-586; S. Szymik, „Żydowska Pascha – Ostatnia Wieczerza – Eucharystia”,Msza Święta – rozumieć, aby lepiej uczestniczyć. Wykład liturgii Mszy(Poznań: Pallotinum 2013) 14-18; R. Pesch, „Das Evangelium in Jerusalem: Mk 14, 12-26 als ältestes Überlieferungsgut der Urgemeinde”, Das Evangelium und die Evangelien. Vorträge vom Tübinger Symposium 1982 (ed. P. Stuhlmacher)(WUNT 28, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 1983) 113-155.

[13]S. Zeitlin, „The Last Supper as an Ordinary Meal in the Fourth Gospel,”Jewish Quarterly Review 42 (1951/52) 251-252.

[14]R. Bartnicki, „Ostatnia Wieczerza nową Paschą Jezusa” 17. R. Bartnicki himself in his earlier publications supported the thesis that the Last Supper was a Passover meal: „Pascha żydowska a chrześcijańska ofiara eucharystyczna. Zarys historii obrzędu”,Studia Theologica Varsaviensia 18 (1980) 1, 97-124; Id. „Ewangeliczne opisy męki w aspekcie literackim, teologicznym i kerygmatycznym”, Studia z biblistyki, III (ed. J. Łach) (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo ATK 1983) 103-143; Id.„Ostatnia Wieczerza a męka Jezusa”, Męka Jezusa Chrystusa(ed. F. Gryglewicz) (Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL 19863) 65-85; Id.„Eucharystia w Nowym Testamencie”, Warszawskie Studia Teologiczne 4 (1991), pp. 14-41; Id.„Eucharystia w Bożym planie zbawienia”, Ruch Biblijny i Liturgiczny 50 (1997) 2-16; Id.To czyńcie na moją pamiątkę. Eucharystia w świetle Biblii(Warszawa: Wydawnictwo ADAM 2010) 7-24.

[15]The Mishnaic tractate Pesachimsays: ‘In every generation a man is obligated to regard himself as though he personally had gone forth from Egypt’(10:5).

[16]N.T. Wright calls it a ‘quasi-Passover meal’; Jesus and the Victory of God(Minneapolis 1996) 556-559. Cf. J. Marcus, „Passover and the Las Supper Revisited”, New Testament Studies 59 (2013) 303-324; B. Pitre, Jesus, the Tribulation, and the End of the Exile: Restoration Eschatology and the Origin of the Atonement(Tübingen – Grand Rapids: Baker Academic 2005) 441-442.

[17]J.D.G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered (Christianity in Making, I; Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 2006) 772-773; M.A. Matson, „The Historical Plausibility of John’s Passion Dating”, John, Jesus, and History, II, Aspects of Historicity in the Fourth Gospel(ed. P.N. Anderson, F. Just, T. Thatcher) (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature 2009) 291-312; P. Fredriksen, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews(New York: Pan Macmillan 1999) 223.

[18]J. Schröter, Das Abendmahl: Frühchristliche Deutungen und Impulse für die Gegenwart(Stuttgarter Bibelstudien 210, Stuttgart: Katholisches Bibelwerk 2006) 44.

[19]‘On the eve of the Passover Yeshu was hanged. For forty days before the execution took place, a herald went forth and cried, ‘He is going forth to be stoned because he has practiced sorcery and enticed Israel to apostacy. Anyone who can say anything in his favour, let him come forward and plead on his behalf.’ But since nothing was brought forward in his favour he was hanged on the eve of the Passover!’ (Sanh. 43a)

[20]R. Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From the Gethsemane to the Grave. A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels(Anchor Bible Reference Library, II; New York – London – Toronto – Sydney – Auckland: Doubleday 1994) 1358.

[21]Philo indeed states that it is impossible to issue verdicts or to carry out executions on days which are festive, but the context might suggest he only means the Sabbath. It is not clear what celebrations the historian of Alexandria actually had in mind; A.-J. Levine, The Misunderstood Jew: The Church and the Scandal of the Jewish Jesus(San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco 2006) 208.

[22]C.J. Humphreys, W.G. Waddington, „Astronomy and the Date of Crucifixion”, Chronos, Kairos, Christos: Nativity and Chronological Studies Presented to Jack Finegan(ed. J. Vardaman, E. Yamauchi) (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns 1989) 165-181; C.J. Humphreys, W.G. Waddington, „Dating the Crucifiction”, Nature 306 (1983), 743-746.

[23]For every of the above arguments a counterargument may be generated. And thus: (1) lack of any reference to eating paschal lamb can be rebutted by the statement that the Jews did not have to use the term ’lamb’ but they spoke of ‘the Passover’ (Ex 12:1-14); C.K. Barrett, „Luke XXII.15: To Eat the Passover”, Journal of Theological Studies 9 (1958) 305-307; J. Jeremias,The Eucharistic Words of Jesus(trans. N. Perrin) (Philadelphia: Fortress Press 1977) 18-19; (2) themention in the Babylonian Talmud does not have to refer to Jesus of Nazareth; J. Maier, Jesus von Nazareth in der talmudischen Überlieferung(Erträge der Forschung 82; Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 1978) 263-275; (3) all actions undertaken on a festive day by the opponents of Jesus can be justified; V. Hamilton, Handbook on the Pentateuch(Grand Rapids: Baker Academic 2005) 194; G. Bucchan Gray, Sacrifice in the Old Testament: Its Theory and Practice(New York: Ktav Pub. House 1971) 386; (4) the fragment of the Mishnah which speaks of the impossibility of issuing verdicts on festive days (Betzah 5:2) refers to the settlement of common disputes by rabbis (like the kashrutlaws, levirate etc.), and has nothing to do with the Sanhedrin; H. Danby, The Mishnah(Oxford: Oxford University Press 1933) 187. The Tosefta in the tractate Sanhedrin (11:7)recommends that executions of false prophets be carried outduring Pilgrimage Festivals – Passover, the Feast of the Tabernacles and Pentecost; J. Jeremias, The Eucharistic Wodrs of Jesus, 78-79; G. Dalman, Jesus – Jeshua: Studies in the Gospels(trans. P.P. Levertoff) (New York: Literary Licensing 1929) 98-100. The Misnah confirms that the sentence can be passed on the eve of a Festival (Sanh. 4,1); R. Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From the Gethsemane to the Grave. A Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels, II, 1361; (5) many astronomers claim that contemporary research cannot determine the content of ancient calendars since they were created on the basis of human observations (this is how e.g. the New Moon was pointed out), and not astronomical calculations; R.T. Beckwith, „The Date of the Crucifiction: The Misuse of Calendars and Astronomy to Determine the Chronology of the Passion”, Calendar and Chronology, Jewish and Christian: Biblical, Intertestamental, and Patristic Studies(Leiden: Brill 2001) 276-296.

[24]The hypothesis seems to be supported by Benedict XVI, who writes: ‘One thing emerges clearly from the entire tradition: essentially, this farewell meal was not the old Passover, but the new one, which Jesus accomplished in this context. Even though the meal that Jesus shared with the Twelve was not a Passover meal according to the ritual prescriptions of Judaism, nevertheless, in retrospect, the inner connection of the whole event with Jesus’ death and Resurrection stood out clearly. It was Jesus’ Passover. And in this sense he both did and did not celebrate the Passover: the old rituals could not be carried out — when their time came, Jesus had already died. But he had given himself, and thus he had truly celebrated the Passover with them. The old was not abolished; it was simply brought to its full meaning.’; J. Ratzinger – Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, Part II,From the Entrance into Jerusalem to the Resurrection(English translation provided by the Vatican Secretariat of State)(San Francisco: Ignatius Press 2011).

[25]S. Hahn, The Fourth Cup. Unveiling the Mystery of the Last Supper and the Cross, p. 108.

[26]D. Daube, The New Testament and Rabbinic Judaism (Peabody: Hendricksons Publishers 1994) 330-332.

[27]Hahn confirms such an interpretation of tasting vinegar in another place of his book: ‘When Jesus takes the Paschal fourth cup, he is suffering on the cross. It is given to him from a sponge attached to a hyssop branch (the same type of branch Moses commanded to be used for sprinkling the blood of the covenant; see Exodus 12:22). Saint John, an eyewitness, chose his words carefully as he described what happened in that moment—and God inspired him in every word he chose.’ (p. 168)

[28]Some exegetes interpret Jesus’ utterance about the Holy Spirit in a similar way: ‘And when he comes, he will show the world how wrong it was, about sin, and about who was in the right, and about judgment: […] in that I am going to the Father and you will see me no more’ (Jn 16:8-10). This means that ‘justice’ – or better ‘justification’ – was achieved at the moment of Christ’s ascension into heaven. Before this moment, the act of justification was not fulfilled; L. Morris, The Gospel according to John. Revised (The New International Commentary on the New Testament; Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 1995) 620.

[29]H.A. Kent, „Philippians”, Expositor’s Bible Commentary with The New International Version of The Holy Bible in Twelve Volumes, XI, (ed. F.E. Gaebelein) (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House 1984) 123-127.

[30]F.F. Bruce, The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to Ephesians(The New International Commentary on the New Testament) (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 1998) 272; A. Skevington Wood, „Ephesians”, Expositor’s Bible Commentary with The New International Version of The Holy Bible in Twelve VolumesXI (ed. F.E. Gaebelein) (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House 1984) 30-31.

[31]M. Rosik, Trzy portrety Jezusa (W kręgu Słowa 1; Tarnów: Biblos 2007) 26-32; Id. Jezus i Jego misja. W kręgu orędzia Ewangelii synoptycznych(Studia Biblica 5; Kielce: Verbum. Instytut Teologii Biblijnej 2003) 253-255.

[32]In response to the request of the sons of Zebedee (Mk 10:35-41; Mt 20:20-24) the cup is directly identified with the death of the Messiah; M. Rosik, Ku radykalizmowi Ewangelii. Studium nad wspólnymi logiami Jezusa w Ewangeliach według św. Mateusza i św. Marka(Wrocław: Polska Akademia Nauk 2000) 92.

[33]For more on the subject, see: S. Mędala, Ewangelia według świętego Jana. Rozdziały 13-21, 256-257.

[34]P.-É. Bonnard, „Pascha”, in: Słownik teologii biblijnej(ed. X. Léon-Dufour) (Poznań – Warszawa: Pallotinum 1973) 646 and 649-651; H. Witczyk, „Pascha”, Encyklopedia katolickaXIV (ed. E. Gigilewicz i inn.) (Lublin: Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski 2010) 1409; Id. „Pascha”, Nowy słownik teologii biblijnej (ed. H. Witczyk) (Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL – Jedność: Lublin – Kielce 2017) 671.

[35]Cf: ‘The Eucharist is the memorial of Christ’s Passover, that is, of the work of salvation accomplished by the life, death, and resurrection of Christ, a work made present by the liturgical action’ (Catechism of the Catholic Church1409).

[36]The idea of the Messianic feast is known from apocryphal apocalyptic literature (The Book of Enoch 62:14;2 Baruch 29:8) and from Qumran writings (1QSa 2:11-22).

[37]R.H. Mounce, The Book of Revelation. Revised (The New International Commentary on the New Testament; Grand Rapids Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 1997) 345-350.

[38]Jesus approaches his death trustfully, aware of the participation in the eschatological feast. The announcement of death has always been connected with the announcement of resurrection (cf. Matt 16:21 etc.)so death does not get the last word. The last word is eschatological fulfillment; A. Paciorek, Ewangelia według świętego Mateusza.Rozdziały 14-28(Nowy Komentarz Biblijny. Nowy Testament I/2; Częstochowa: Edycja Świętego Pawła 2008) 562.

„Scott Hahn, The Fourth Cup. Unveiling the Mystery of the Last Supper and the Cross, New York: Image 2018. Polish edition: Scott Hahn, Czwarty kielich. Odkrywanie tajemnicy Ostatniej Wieczerzy i krzyża (trans. D. Krupińska),Kraków: Esprit 2018. Pp. 191. Zł 26.90. ISBN 978-83-66061-68-2″, Biblical Annals 9 (2019) 3, 569-590.

tłum. M. Konopko

PDF znajdziesz tutaj